Santa Cruz Mountains: One AVA, Too Many Worlds

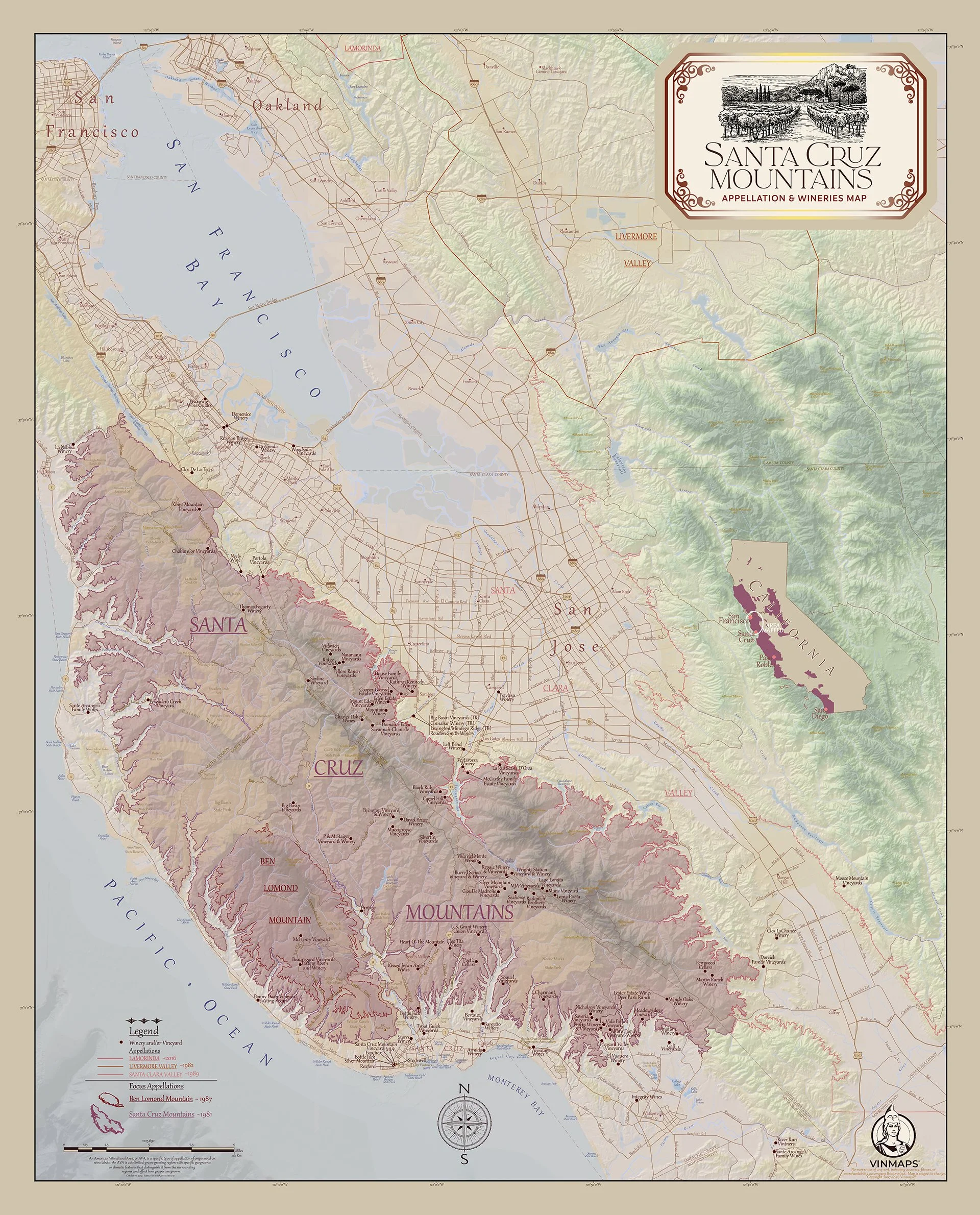

The Santa Cruz Mountains AVA is often described as one of California’s most distinctive wine regions.

That’s true — but also incomplete.

What’s rarely said out loud is that it may also be one of the most internally diverse appellations in the country. Diverse to the point where the single-AVA structure starts to feel less like protection of place, and more like a blunt instrument.

Corralitos feels like a world away from Los Altos Hills.

Ben Lomond doesn’t farm, ripen, or drink like Summit Road.

And yet, all of it lives under one name.

Ben Lomond Mountain was even proposed as its own AVA in 1987 — a reminder that this diversity has been recognized for decades, even if it was never formally adopted. Wine maps can be purchased here

A forward-thinking AVA that outgrew itself

When Santa Cruz Mountains was federally approved in 1981, it was ahead of its time. Rather than following county lines, it was defined by mountainous land above roughly 400 feet on the western side, and 400–800 feet on the eastern side.

That made sense then. It still does.

But forty-plus years on, the region’s understanding of itself has deepened — while the appellation structure has remained static.

Today, this one AVA spans:

three counties

elevations from ~400 to over 2,600 feet

maritime western slopes and warmer eastern rain shadows

redwood forests, decomposed granite, clay loam, and limestone seams

In almost any other wine country, this would already be several named places.

A personal moment that clarified the problem

I ran into this head-on when submitting a label to the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau for a Pinot Gris sourced from Corralitos.

Corralitos felt like the most honest descriptor. It is its own distinctive part of the AVA, and it actually helps explain the wine to the consumer. It’s a world away from our Los Altos Hills vineyard — as different, in my mind, as McLaren Vale is from the Adelaide Hills.

The response came back simple and procedural: “You can’t put a sub-region on the label.”

Not this sub-region.

Not unless it’s federally recognized.

They weren’t wrong — but the moment stuck with me.

Perspective from New Zealand: small places, real meaning

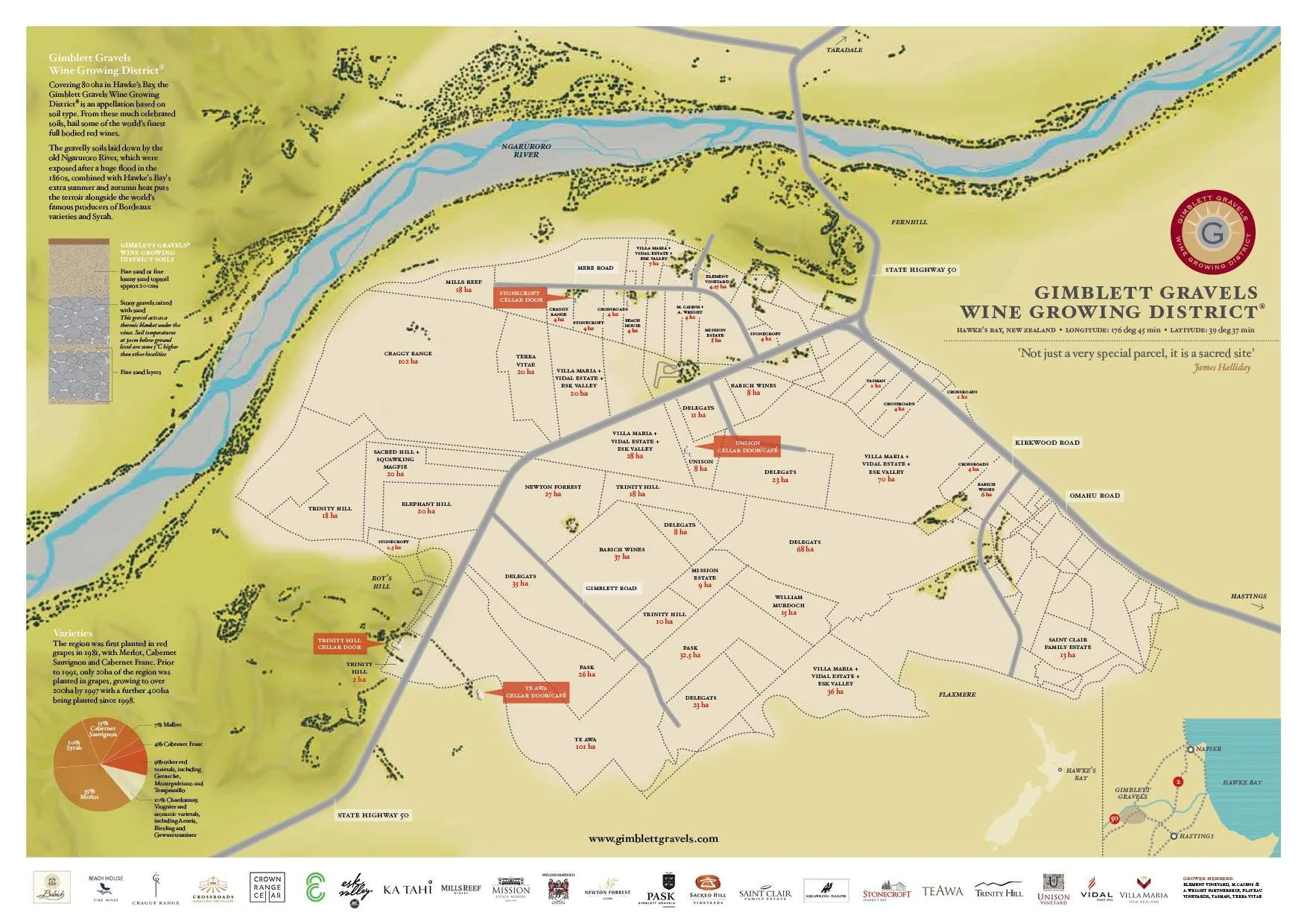

Coming from New Zealand, the contrast is stark.

In Hawke’s Bay, Gimblett Gravels and the Bridge Pa Triangle sit side-by-side. You can farm both within minutes of each other.

Yet they’re treated as distinct places because the soils, drainage, and resulting wines are genuinely different.

To put scale on it:

Gimblett Gravels covers roughly 800 hectares (≈2,000 acres)

Bridge Pa (Ngatarawa) Triangle is larger, but still only a few thousand hectares

Both are tiny when set against the Santa Cruz Mountains AVA, which spans roughly 480,000 acres across three counties.

And yet those New Zealand sub-regions are named, accepted, and understood.

That’s not marketing creep.

That’s precision.

Gimblett Gravels Wine Growing District

Napa Valley: sub-regions as clarity, not clutter

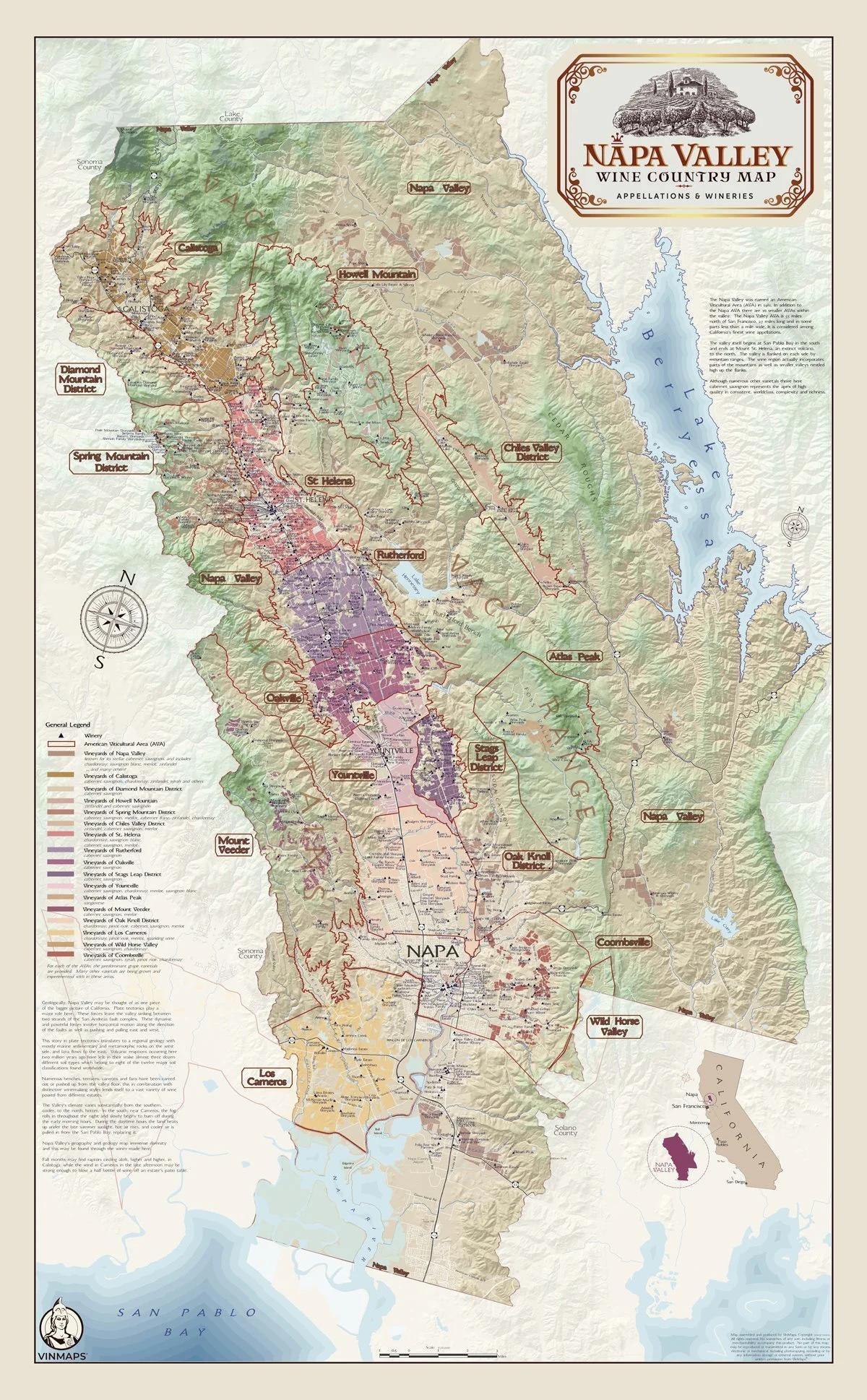

The Napa Valley AVA offers another contrast.

Napa is smaller than Santa Cruz Mountains in overall footprint, yet it contains 17 (as of Jan 2026) recognized sub-AVAs — Oakville, Rutherford, Howell Mountain, Coombsville, among others — each with a clearly communicated identity.

No one argues that sub-AVAs dilute Napa’s reputation.

They sharpen it.

They allow producers to say where within Napa a wine comes from — and allow drinkers to build understanding over time.

Napa Valley AVA with its nested appellations. Wine maps can be purchased here.

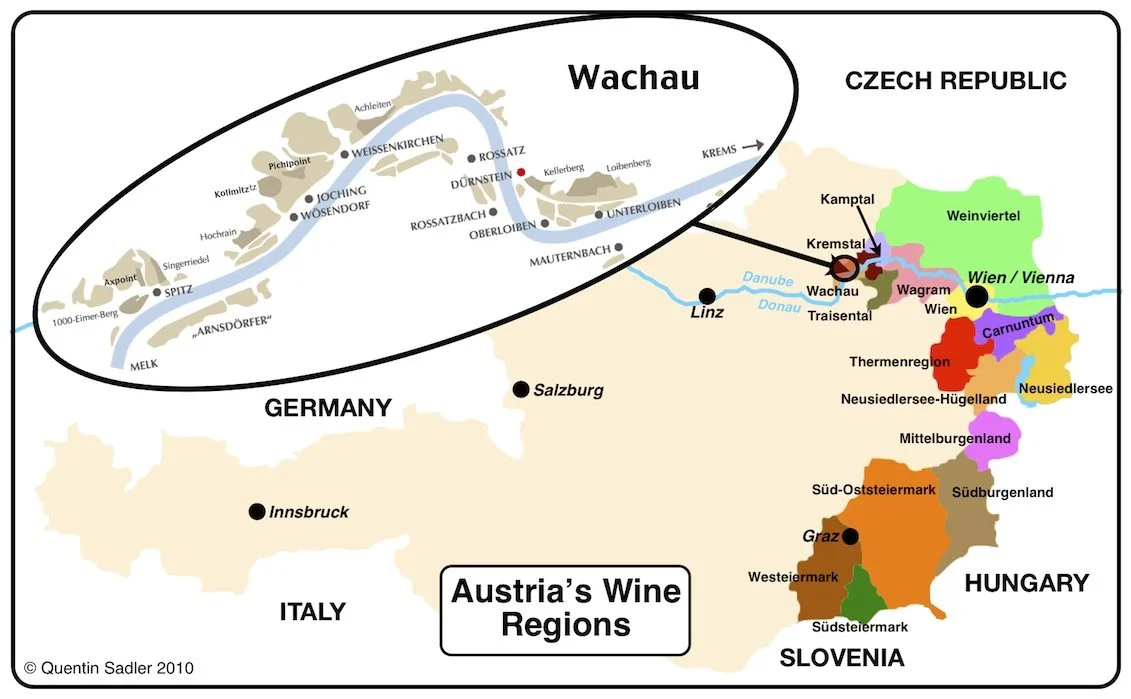

Austria’s Wachau: when enforcement creates trust

Then there’s Wachau DAC.

The Wachau’s modern appellation rigor was shaped by hard lessons — including the 1985 Austrian wine scandal, when a small number of producers adulterated wines with diethylene glycol to simulate sweetness and body. The fallout was severe and nearly collapsed the country’s export market.

The response was equally severe.

Austria rebuilt its wine laws around strict enforcement, on-site inspections, and clearly defined categories. In the Wachau, vineyard designation, harvest timing, and cellar practices are actively monitored. Miss the mark, and the wine is declassified — no negotiation.

That history explains why Wachau classifications carry real weight today. Not because they’re romantic, but because they’re enforced.

Back to Santa Cruz Mountains

Through decades of farming, tasting, and comparative observation, growers and viticulturists have informally identified distinct sub-regional personalities within the Santa Cruz Mountains:

Skyline

Summit Road

Coastal Foothills

Ben Lomond Mountain

Saratoga / Los Gatos

Corralitos / Pleasant Valley

These distinctions weren’t dreamed up by marketers or committees. They emerged slowly — from people comparing wines year after year, vintage after vintage, across elevation, exposure, and soil.

That said, even this framework is likely too broad.

The moment these ideas are pushed toward formal definition, the challenges become obvious. Boundaries would need to be drawn. Sites would be included or excluded. Names would be debated. Arguments would follow. A can of worms would be opened.

The Santa Cruz Mountains already knows this uncomfortable truth: it isn’t one place. And any attempt to codify its internal differences will force long-standing, largely unspoken knowledge into the open — where consensus becomes much harder to maintain.

What’s missing isn’t understanding.

It’s formal recognition.

Vineyard on Summit Road

The uncomfortable scale question

Once you accept an AVA this broad, you start asking awkward questions.

If Corralitos can’t be named, why does the entire mountain chain get a single identity?

And if scale alone isn’t a limiting factor, at what point do you simply absorb Santa Clara Valley AVA while you’re at it?

That sounds flippant — but structurally, it’s the same logic.

Why this matters

This isn’t about adding words to labels.

It’s about honesty of place.

When an appellation becomes so large that meaningful distinctions can’t be named, it stops clarifying origin and starts flattening it. Producers end up explaining their wines manually, bottle by bottle. Consumers are left with reputation instead of understanding.

Santa Cruz Mountains doesn’t suffer from a lack of identity.

It suffers from too much identity for one box.

Closing thought

Appellations work best when they evolve alongside knowledge.

Santa Cruz Mountains was visionary in 1981.

Today, it’s ready for its next iteration.

The mountain hasn’t changed — our understanding of it has.